(Editor’s note: For the duration of this piece, I refer to what we Americans call “soccer” as “football.” Just know that’s what the rest of the world calls it, and we’ll get through this together. Also, I’ve made the narrow-minded choice to think of England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Ireland as The United Kingdom. I’m well aware that Ireland is not under the UK umbrella anymore, and that independence didn’t come easy. But Irish players have been so readily accepted in the English game, I thought it unnecessary to sort them out. As someone who’s Irish, Scottish, and English — in that order — I urge us all to unite. If not forever, then at least for the next 10,000 words.

Oh, about that. This block of writing may not be meant for one sitting. Even the Editor’s note is pretty long. For your benefit, I’ve broken it up into three parts. As always, thanks.)

Arsenal FC – The United Nations of Football

Prologue – Come gather ‘round people

Oh, about that. This block of writing may not be meant for one sitting. Even the Editor’s note is pretty long. For your benefit, I’ve broken it up into three parts. As always, thanks.)

Arsenal FC – The United Nations of Football

Prologue – Come gather ‘round people

On the first day of October, 1884, it was made official. The 25 countries doing the most international business created the Prime Meridian. Though sailors had already followed it for some time, from that day forward modern man would tell time and his place in the world by where he was in relation to an imaginary line that ran through the Royal Observatory in Greenwich. (For the purposes of this essay, you’ll do well to remember that France abstained from the vote and did not play along until 1911.)

But the times, they are a’ changin’. Literally. The earth tilts on its axis and swings in its orbit, always losing a battle to gravity and slowing down. We use atomic time now, far more precise, and we add leap seconds when needed. The Royal Observatory and its imaginary line are quaint symbols of a bygone era.

I’ve got a map on my wall. A big, flat thing, a few feet across. In the center floats the Queen’s island. And there, in its southeast corner, where the Thames drains toward Europe, sits London.

We know the earth is not flat, not when seen from a distance. But it’s hard to imagine. Up close, from here on the ground, you can’t see the curve. And to you it seems like the center of the world is where you’re born, where you are or whereever it is you're going next.

How many of us can look at a big flat map and see it all at once? How many of us can look at a flat horizon and imagine something beyond it?

…

Part I – The young cartographers of North London

The curve

If you were looking for the center of the football world, still today, you could do worse than North London.

There’s dispute over which building exactly, but you could hazard a guess at the pub where a group of competitive men held meetings in the fall of 1863. Over some number of pints, they wrote most of the rules to the modern game of football. (The rougher of them split off to form rugby, and their misshapen ears would never forgive them.)

If you stood outside that same pub today you could, with a bit of luck and the wind at your back, kick a ball and watch it roll and carom into the neighboring borough of Islington, to the district of Holloway, and up to the gates of Emirates Stadium. That’s where they are. You might consider them just a team, and him no more than a manager. And if, at the end of this writing, you remain convinced that they are and he is, so be it.

But I believe Arsenal Football Club and its French coach, Arsene Wenger, are something more. I struggle to find an apt label for them. I don’t know how large a force they have been, or can be. All of that is left for history.

I believe, though, that they perform some act beyond football. And that they are actors beyond players and coach, and that their field of play extends beyond North London, and, indeed, beyond the field of play. It’s a bit abstract. And yet I have faith.

After all, I can’t see the curve of the earth. But I believe it’s there.

This is a story about a revolution.

…

From bad to tragic

Sometime during the 16th century, we started to get a pretty good idea of what the earth looked like. Couple oblong landmasses running east to west, each stretching south where — through Panama in the West and Egypt in the East — they connected to oblong landmasses that ran north to south. Sprinkle a couple hundred islands, including a couple just off France’s west coast, and that’s pretty much everything that’s floating out there.

I’m in awe of the ancient cartographers, whose endless series of perilous explorations, precise measurements and long-hand calculations produced drawings that hardly anyone believed. More awesome, though, is their accuracy. When we finally got far enough away from earth to get a good look, it turns out that some of them were pretty close.

But the cartography that took place in the last 200 years has been less impressive. Since we figured out what the landmasses looked like, we began to divide them with imaginary lines. We called them countries, colonies, protectorates. Just as post-Columbus mapmaking succeeded, post-Napoleon mapmaking failed.

How stunned the Pamlico Native Americans would have been to learn that not only had they been living in the colony of North Carolina, but they’d all be dead before it got statehood. Think of the reaction of an enormous chunk of West Africa, occupied by speakers of 450 different languages, at an announcement made with a British accent in 1914.

“From this day forward, you are Nigerians.” (Clears throat.) “Yes, all of you.”

Israel. Iraq. Serbia, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia. Liberia, not to mention the rest of Africa.

Perhaps no one carved up and labeled more land than the Brits, who thought themselves a benevolent force. Though their hearts were usually in the right place, their lines were not, and the results have ranged from bad to tragic. As it turns out it’s hard to draw an imaginary line, and harder still to see it.

…

Fish and guests

To tell the story of Arsenal’s team is to tell the story of different places.

Consider Francesc Fabregas. The lynchpin midfielder, only 20, is by some measure the most exciting thing to come out of the sleepy Spanish village of Arenys del Mar. Were he not able, and willing, to complete a pass to any player at any time, Fabregas would likely work at the docks of this tiny fishing outpost.

Consider Robin Van Persie. The mercurial striker, 24, hails from Arenys del Mar’s antonym, the massive port city of Rotterdam, in the Netherlands. Again, it’s likely he’d be loading or unloading boats if he didn’t have a vicious left foot.

It’s an interesting dichotomy. But some places demand closer inspection.

Emmanuel Adebayor, 23, is a lanky striker from Lome, Togo. After curing his longstanding case of the goalmouth yips, Adebayor has used this season to produce a carbon copy of the fantastic season Didier Drogba had last year, 25 yard volleys and all.

Togo is a doomed little strip of land wedged between Benin and Ghana. Only 31 miles wide and 100 miles long, a determined American tourist family could cover the whole of Togo in one day. But why would they?

A former German colony, it went to the French under the Treaty of Versailles. After France relinquished control in 1960 Togo elected its first president, the Brazilian-born Sylvanus Olympio. The president sought a friendship with the young American, John F. Kennedy.

Eleven months before Kennedy was shot in Dallas, Texas, Olympio was hunted down and killed outside the American Embassy in Lome. His assassination marked Africa’s first post-independence military coup.

Olympio’s brother-in-law Nicolas Grunitzky, who played no part in the coup, took over. But when Grunitzky allowed multi-party democratic actions to resume, he was deposed by the same group that had killed Olympio. (Grunitzky opted to avoid the bullet, and the coup was bloodless.)

In Grunitzky’s wake, power fell to a single man: Gnassingbe Eyadema, one of Olympio’s assassins. Sadly, Eyadema was kind of an asshole.

He took power in 1967. In a move that would have drawn admiration from his American counterpart, Dick Nixon, Eydema sufficiently disbanded all political opposition by the time another election was held in 1972. As the only name on the ballot, Eyadema got 90 per cent of the vote, and all tyrannical hell broke loose.

Since ’72 there has been much Togolege fear and loathing of Eyadema, mostly because his thugs left hundreds of bodies on the campaign trail.

Sylvanus Olympio’s son, Gilchrist, rose to prominence as an opposition candidate before the 1993 election. In a terrifying episode of de ja vu, Eyadema’s son, Ernest Gnassinbe, led a group of men as they made an attempt on Gilchrist’s life, effectively scaring the young Olympio off to France.

Eyadema went on the win the 1993 election, with a post-election analysis finding that ballot boxes had been stuffed with the names of dead voters. (Campaign slogan: “Vote Eyadema, or else you’re dead, and then you’ll be dead and still vote Eyadema!”)

Eyadema won every election he ever ran, right up until his death in February of 2005.

His death brought on another Togolese tweak on democracy, when the army bypassed the constitution and installed — you guessed it — one of his sons, Faure Gnassinbe. When Gnaissnbe’s appointment was contested he threw together a quicky election, to be held only a couple months later. (Comparatively, Ponce de Leon landed in Florida 487 years before its chads were hung.)

Amid echoes of his father’s tactics, Gnassinbe won that election thanks to hundreds of thousands of votes — in a country of only five million — from people who do not exist.

During his 38 years in power Eyadema allowed his country to be significantly isolated and sanctioned toward its economic death. By the mid-90s Togo’s economy was almost entirely based on fishing and farming. (Apparently they missed out on the dotcom boom.)

We can romanticize fishing as much as we want, but I hope no one holds any illusions about the reality of plantation work. By the way, in the deep waters off Lome, fisherman pull up a good number of white fish, shrimp and, for a while, the corpses of Eyadema’s political enemies. Two other wrenches thrown into Togo’s economic future: 1.) its education system’s not too big on teaching womenfolk to read, and 2.) Togo’s HIV-AIDs strategy seems to be quiet denial.

And I would never have accused Eyadema of arms trafficking and trading in blood diamonds. No, no. Not while he was still alive. And I wouldn’t worry about what his kids will do with the country’s newfound oil wealth. Not at all.

Back to young Mr. Adebayor. The son of Nigerian immigrants, it’s likely that Adebayor’s father — an educated man who wanted his son to be a doctor — lived through his own country’s horrific internal strife in the late 60’s, only to find himself in the middle of Togo’s.

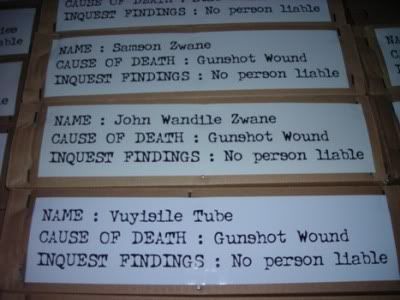

After the 2005 elections, young protestors flooded the streets of Lome. Togolese security forces opened fire on the country’s youth in some cases, and in others executed dissidents with machetes or spiked clubs. We are not in Kansas anymore, Togo.

Adebayor would have been 21 at the time of the protests.

Given his charisma and reputation as an outspoken young man, unwilling to do as he’s told. . .where would Adebayor have been during that election year without his talent? Make your own judgments. But all the other indignant young men of his country? Togo’s next generation of free thinkers and revolutionaries? They’re all dead.

From one of the most oppressive capitol cities on earth to one of the least: Tomas Rosicky, 28, was born in that European lighthouse of rebellion, Prague. While under German occupation during the Second World War, Prague was the site of two outrageous acts of revolt. First, the 1942 assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, a chief Holocaust architect tipped as Hitler’s successor, by a pair of Czech dissidents.

And then, in early May of 1945, the people of Prague heard that the Allies were slowly liberating Europe. Encouraged by the news, the Czechs would have known that any day Russian tanks would roll in and send the Germans running. But Prague decided not to wait, and over a period of days, liberated itself.

These events were not out of Prague’s character. It seems to be a city of perpetual revolution. Liberal-minded writers and politicians of the 60’s sewed the seeds that would end Soviet rule, and the Czechs made good on those ideas in 1989 when half a million protesters filled the streets of Prague in the Velvet Revolution.

Now, the Czech Republic finds itself in a renewed tug-of-Cold War between Russia and the United States. As Russia rearms itself on a grand scale and George W. Bush seeks to install a missile defense system in the Czech Republic, Prague is thumbing both of the traditional powers in the eye. While largely ignoring Putin’s Russia, the Czechs fought Bush’s radar plan for as long as they could. They’ll put it in, though I wouldn’t be surprised if some days they forget to turn it on.

Recently, the Czechs became part of a growing European block that doesn’t even check for passports at the border.

Aleksander Hleb, 27, was born in Minsk, Belarus, or, as I like to think of it, Little Moscow. Hleb is Rosicky’s midfield counterpart and absolute mirror in footballing terms: lithe, highly skilled, offensive minded, a smart distributor and hard worker who occasionally snaps off a goalbound shot. But while Hleb is left-footed, and Rosicky is right-footed, the politics of their respective countries are reversed. Rosicky’s Czech Republic trends toward the far left, while Hleb’s Belarus is leaning so far right it’s in danger of falling over.

Belarus, decimated under German occupation during World War II, was liberated by the Russians in 1944 and never allowed to forget it. This substantial block of land was chipped off the Soviet Union in 1991, but when they pulled back the Iron Curtain, they found an aluminum one. Belarus remains under the Kremlin’s thumb to this day.

The country has been handled, at least in theory, by Alexander Lukashenko since 1994. Lukashenko is not a tyrant, but he’s well on his way.

He should have faced re-election in 1999, but decided to push the election back to 2001. He won reelection in the Putin-esque manner of limiting any serious opposition. Then, in 2004, he again meddled with the constitution, this time to allow himself to run for a third term. He won an election that was as transparent as the Berlin Wall.

My brother-in-law is Polish, and he spent much of his youth driving a small car at high speed to different spots in central Europe. So I was stunned to learn that despite his proximity, he’d never once set foot in Minsk.

“I would never go to that country and give my money to that government,” he said.

And, indeed, the government is where the money goes. Lukashenko is systematically acquiring Belarussian businesses and covering his tracks by cracking down on the press. He’s also limiting political opponents as he builds toward absolute power.

How bad is it? In my country, we’ve decided that the worst we’ll do is frown when an American burns his own flag. In Belarus, you can’t even wave the flag of the Belarusian People’s Republic, the short-lived democracy of 1918 that emerged during World War I. The Russians toppled that government and installed their own, and now you face a penalty if you so much as wave one of their flags in Minsk.

By the way, some of the leaders of the Belarusian People’s Republic escaped capture and formed a government in exile. It still exists today, right where they formed it all those years ago, in Prague.

. . .

War and peace

Phillipe Senderos, 23, was born in Geneva, Switzerland. Senderos is an enormous defender, only slightly smaller and bulkier than the Alps.

Ah, the Swiss. Nice to get away from all that revolution and war, right? Here you can be taken in by the charm of fine watches, diplomacy and skiing.

Switzerland gained its independence from the Romans in 1499, and for the last 500 years has basically asked the rest of Europe to leave it the hell alone. But, it’s offered itself as a mediator and a gracious host. The League of Nations was based in Geneva, as is its offspring, the United Nations, and a handful of well-meaning non-governmental organizations.

You’ll be surprised to learn that military service is mandatory for the Swiss. At age 19, each male must enlist and serve for at least 260 days. I assume those 260 days are spent learning how to ski very fast.

Nicklas Bendtnder, 20, hails from Copenhagen, Denmark. Copenhagen, a city of just a million people, can claim two of the smarter humans in the last couple hundred years. Soren Kierkegaard, the 19th century philosopher, and one of his fans, Niels Bohr, 20th century physicist.

Kierkegaard was an advocate for the separation of church and state. He went beyond that by some degree when he argued that the church itself, even filled with parishioners, was a vacant institution. It says something for the Danish that Kierkegaard died of natural causes.

Kierkegaard’s collected writings allowed him to have a postmortem conversation with the German Fredrich Nitzche. Bohr, the physicist, was able to have a real, live conversation with a German heavyweight: Albert Einstein. Einstein was known to be personable, but Bohr would have been one of the few people he’d ever met with whom he could really lock eyes and feel understood.

How brilliant was Bohr? Not only did he win a Nobel Prize for physics, his son did. (What have you and your dad done?)

Other than these intellectual giants, that’s about it for Denmark. Like Switzerland it has compulsory military service for males and like Switzerland it doesn’t make war. It’s been a long time since there was something rotten in the state of Denmark.

In polls that rank the most livable cities in the world, Geneva and Copenhagen consistently rank in the top five.

From two of the most peaceful cities in the world, let’s go to two of the least.

If you don’t know the Ivory Coast’s history, here’s the short version: take Togo, change the name of the military dictator, add a large, well-armed opposition in the country’s North, and shake well.

Habib Kolo Toure, 27, and Emmanuel Eboue, 23, are among the litany of West African players who stopped off in Belgium to tryout for professional teams, before eventually being routed throughout Europe to prestigious clubs. Eboue and Toure left Cote d’Ivoire — though I prefer the term “escaped” — in 2002, just when the country’s civil war was “ended” for about the fifth unsuccessful time. Its embers are still flickering.

Here’s where we pivot into the surreal. Eboue, a Christian, was born in Abidjan. The capitol city, an expanding metropolis, Abidjan is home to the country’s administration, three million of its people, and a growing number of armed street gangs.

Toure, a Muslim, was born in Bouake, the stronghold and de facto capitol of the Rebel North. Yes, that’s right. For large chunks of his time at Arsenal, Arsene Wenger has started, in tandem, two centerbacks who represent opposing sides of Cote d’Ivoire’s Civil War.

And if you’re wondering about the Ivory Coast’s policy for military conscription, it goes like this: if you can hold it, you can shoot it.

How bad is it in Cote d’Ivoire? Toure and Eboue impressed at their tryouts in Belgium, but others who were not so prodigious simply refused to go back home when they were dismissed. Many of them ended up working as prostitutes.

Wenger has also founded his success on a number of French players. He has an affinity for those who’ve passed through the Clairfontaine, which is sort of like saying you like to buy your art at the Lourve.

But Wenger’s brightest, fastest shooting star today is teenage phenom Theo Walcott, born about 15 tube stops away from Emirates Stadium in Northwest London.

Arsenal FC are a collection of 35 men from 18 countries. To spell their names you’ll need seven accent marks, an umlaut, an L with a stroke and an A with a ring. They hail from seven capitol cities, one rebel capitol and the capitol of a government in exile. They’ve come from the Gulf of Guinea, the Bight of Benin, the Baltic, the Mediterranean, both sides of the Atlantic and both sides of a Civil War. From the wildly integrative Paris and Prague to the line-in-the-sand divided Ivory Coast.

We know how they got to North London; their skills carried them. But who brought them there? And why?

. . .

The roots of tolerance

Consider Arsene Wenger, 58, born in Stasbourg, four years after liberation, three years into the Fourth Republic and nine years before the birth of the Fifth. Wenger saw rapid changes in his country. Most notably France renounced its colonial role in Africa and was on the leading edge of the African independence movement.

But this came only after a bloody battle for Algerian independence. The Algerian War was a bad war, fought badly, and it taught France what America did not learn from Vietnam: war is hell, and should be avoided. Since that time, France has made limited military moves: protecting Kuwait in the first Gulf War, hunting terrorists in Afghanistan, and a vital peacekeeping role in the Ivory Coast.

After decolonization, France made significant steps to the left politically, though not without a bit of poking from its youth. In 1968, when Wenger was 18, France was a thunderhead of rebellion. In May of that year, one month after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination touched off nationwide riots in America, French student and worker protests called for civil rights, fair treatment of workers and the ouster of Le General, Charles de Gaulle.

Though they failed in overthrowing de Gaulle, he stepped down a year later.

By 1977, when Wenger was a 28-year-old professional benchwarmer in Strasbourg, France had pulled up all of its flags save for the one in Paris and a handful of peaceful, near-autonomous colonies. Today France is so far removed from its colonial past that it doesn’t take an ethnic count in its census.

But even if Wenger had embraced civil rights and rejected racism, there are further explanations to why he might embrace a multinational football team.

France’s greatest player of the 1980’s was the decidedly unFrench-sounding Michel Platini, a curly-haired midfielder whose parents were Italian. Its greatest talent in the 1990’s was the even-less-French-sounding Zinedine Zidane, a Muslim, the son of Algerian immigrants. Its greatest player in the new millennium is forward Thierry Henry, whose parents emigrated from two of the remaining French colonies, Guadeloupe and Martinique.

Though he’s flourishing at Barcelona, Henry’s finest years came as the conductor of Wenger’s symphony in North London. But for all his wizardry, his best move came off the field. He’s the head of Stand Up Speak Up, Nike’s anti-racism foundation. (Let’s be clear: Henry did not just lend his name to Stand Up Speak Up. It was his idea, and will define his post-career life.)

As players of foreign ancestry, Henry and Zidane are not the exception on the French national team. Since it was integrated in 1931, the team has progressively grown more accepting of foreign players. The 2006 squad which reached the World Cup Final was largely built on men of African and Carribean descent, along with the Algerian Zidane and Vikhash Dhorassoo, whose ancestors were Indian. And among the white players of French ancestry was Franck Ribery, a converted Muslim. (It is believed that France’s population could soon be 15 per cent Muslim, but who’s counting?)

And it may turn out that another convert is Wenger’s greatest achievement, as a coach or as a man. While at Monaco, Wenger signed an unknown young forward, one who bore a most unfortunate label: African Muslim.

George Weah, then 22, had torched Liberian and Cameroonian defenses in his young career. But, given the dearth of top drawer African players, it was unclear how his skill would translate in Europe.

Well, 55 goals at Monaco, 53 more at Paris St. Germain, 58 more, and a World Player of the Year Trophy at AC Milan. . . translation? C'est magnifique.

Weah’s success gave him great opportunity. At one point, when Liberia was a shitstorm of bullets and its government in shambles, Weah was funding the national team out of his own pocket. Weah’s generosity, as a wealthy man in a country — hell, a region — of little wealth, is legendary. I can offer a personal anecdote.

My girlfriend’s brother teaches at the same school as a Liberian who is close friends with Weah. Some years back, Weah bought this friend a car. When it broke down, he did it again. And again.

Weah can also be held up as a symbol for religious unity. (Which trails only education, food, malaria nets, and anti-retrovirals on Africa’s wish list.) As an adult, Weah converted from Islamic faith to Christianity, though without bitterness.

“It’s not good for Muslims and Christians to fight each other,” Weah said. “We are one people.”

Though they parted ways with George’s move to Paris, the Liberian player and his French coach remain close to this day.

“Wenger made me not just the player I am today, but the man I am,” Weah said.

If the roots of intolerance are easily traced — a violent episode, a stirring speech of vitriolic undertones, or even overtones — than the roots of tolerance are much subtler, and nearly invisible. The thread of acceptance is sewn with a fine needle.

Is it a decision? Or is it the lack of a decision? “When did you begin not to hate?”

. . .

Part II – The flood

The roots of intolerance

When Arsene Wenger took the job at Arsenal, he, and Arsenal, were crushed in the English tabloid press. “Arsene Who?” asked the London Evening Standard. It was a fair question.

George Graham had restored the once-prominent club in the late 80’s and early 90’s, but since his departure in 1995 Arsenal was in freefall. Four coaches, three of them “caretakers,” had inspired little optimism and not taken much care in the previous two years.

At that time, there was only manager in the league born outside the United Kingdom, Ruud Gullit, who had just been named player-manager at Chelsea. Of the other three foreign coaches in the top division, in the history of English football, none had lasted into a second season.

The other leading candidate for Arsenal’s job was also a foreigner, but of a different stature. Johan Cruyff was the greatest Dutch football player of all time, and had more recently been the most successful coach in Barcelona’s history.

Wenger, meanwhile, had won a French League Title and a French Cup with AS Monaco, but after the club fired him he was lost in the relative obscurity, at least in football terms, of Japan. Before he was rumored as the next manager, most Arsenal fans were unaware of Arsene Wenger, the coach, and probably Arsene, the first name.

Who indeed?

Wenger spent his playing career as an unused defenseman. “I was the best player in my neighborhood growing up,” he said. “But it was a small neighborhood.” Fluent in four languages, he spoke bits of three more. Its much better now, but in 1996 his English was an accented murmur that seemed to strain his tongue.

If the press had trouble understanding what he said, Arsenal’s squad was more troubled by what he did not say. The Premier League was dominated by the fiery Scot, Alex Ferugson, who helmed Manchester United with all the coolness of a smokestack.

Arsenal’s players, then, were made uneasy to hear the rustling of shorts and the thump of shoe meeting ball. No yelling. Though he instructed on style of play, Wenger was a friendly, even timid figure in practice. His halftime speeches, even when the team was losing, were often subdued. Abstract, even.

More incredible still were his off-the-field instructions: no drinking before big games, no more Sheperd’s pie and fried foods, and hit the treadmill now and then, preferably now. He brought in French players who followed the same edict, and convinced his English core to do the same. (Given that some of them were admitted alcoholics, he may not have only added years to their careers, but their lives as well.)

Wenger also adopted a policy of worldwide scouting, which he’d done at Monaco. None of this would have mattered, though, had Wenger failed.

. . .

What, and with whom

Consider Eric Cantona. If intolerance is seeded by a single event, Cantona carried out the act that began to tip the scales in English football.

And I don’t mean his flying kick at a front-row heckler. Though villainous, the English embraced the attack in all its scandalous glory. England had no problem with a foreigner coming into its league and misbehaving. Scoring landmark goals, though? That’s going too far.

In May of 1996, Liverpool and Manchester United met in the Football Association Cup Final. Of the 26 players to reach the field for either side, only two were not born in England, Scotland, Ireland or Wales: the Dane, Peter Schmiechel, United’s giant goalkeeper, and Cantona, the Frenchman. After 85 scoreless minutes, a Manchester corner kick was punched 20 yards out to Cantona, whose shot fluttered untouched into the net.

Manchester United 1, Liverpool 0. English football would not be the same.

Cantona’s goal was not the first important play made by a foreigner in English football; far from it. (He also scored two in the 1994 FA Cup win.) But it represents the moment when a wise man looks at a growing pool of water on the dry side of a dam and says, “Well, that’s new.”

In the first 112 years of the FA Cup Finals matches, spanning some 300 goals, only four were scored by someone not born on the British Isles. Including Cantona’s Cup-winner, 13 of the last 23 goals scored in FA Cup Finals have been converted by foreigners. In seven of the last 12 games, no UK representative has made the scoresheet. (Nobody scored in the 2004 Final, but six of the nine penalty kicks came from foreign-born shooters. The one miss came from Paul Scholes, an Englishman.)

They’re not just scoring, either. They’re everywhere. Chelsea FC won the 2007 FA Cup with a roster of six Brits and 10 non-Brits, with Didier Drogba, the Ivorian, scoring the game’s only goal.

The floodgates were opened. It flooded.

But a few months after Cantona’s goal something happened that made the change come harder and faster. A French coach signed with Arsenal FC. And it did matter, because Wenger did not fail.

In 50 seasons from 1947 to 1997, Arsenal won the Premier League five times and were runners-up only once. In the 10 seasons since Wenger’s arrival, Arsenal’s topped the league three times and finished second four times. Arsene has already equalled the previous 50 years’ tally of FA Cups, with four.

You could say Arsene Wenger’s reputation starts and ends with Arsenal’s perfect 2003-2004 season. The last time there had been an undefeated season in English football, the Queen was. . . well, she was named Victoria. It was 1889.

But Wenger’s bold streaks only start there. In 2006, Arsenal swept through 10 UEFA Champions League games and a total of 995 straight minutes without surrendering a goal. Two years prior to its undefeated run of 49 games, Arsenal had strung together 30 without a loss until a precocious English teenager named Wayne Rooney, then playing at Everton, beat them in the final minute.

And this season, Arsenal rolled through 15 unbeaten games before dropping one to Middlesborough. Since then? Twelve league games without a loss. But Arsenal is not just trying not to lose: its flowing movements forward are compelling stuff.

Even those who complain that the Gunners are trying to play “perfect” soccer have to shut up when four, five, and six players make intertwining runs and passes that leave a ball in the net, a goalkeeper on his ass and parts of North London in hysteria.

As interesting as it is to look at how Wenger’s succeeded, what should not be ignored is with whom he’s done it.

His two best forwards, those who keyed the 30 and the 49, were the Dutch genius Dennis Berkgamp and the Frenchman Thierry Henry, who equaled Berkgamp in skill and surpassed him in speed. At various times, Wenger has won with a German in goal, a Spaniard in the middle, a Dutchman and a Swede out wide. Africans at the back, Africans up front. Brazilians in the middle, a Brazilian-Croat up front, and Frenchmen all over.

In February of 2005, Arsenal became the first English team to play a game without an English player on the field or on the bench. They crushed Crystal Palace that day, 5-1.

Arsenal are not the only team trafficking in the skill exchange rate. Every top Premier League scorer in the new millennium has been from outside the UK. Last year, the Kingdom had only three players in the top 10 goalscorers, and none in the top three. This year, nine of the top 10 scorers are African, South American, or from the European mainland. The top four scorers are Portuguese, Togolese, Spanish and Zimbabwean.

There is, however, one area where Brits reign supreme. In 2005-06, eight of the 11 players who topped – or bottomed – the league in player discipline were Irish, English, Scottish or Welsh, including the top three. In 2006-07, it was eight of 12, including four of the top six. This year, it’s nine of the top 12 spots, including the top three.

I sometimes find malice in English tackles, and many are dissected in great detail. (Including a recent high-profile case involving Arsenal, to be discussed later.) But typically, I don’t think players who accumulate yellow cards should be thrown out of the league because they’re violent. I think they should be thrown out because they’re slow and they stink.

Arsenal’s chief rivals during Wenger’s 10 years have been Chelsea, with two Premier League titles, and Man United, with six. In the same period, Liverpool has hovered around the top of the table, won two Carling Cups, and appeared in three FA Cup Finals, winning two. Each of these teams is on the leading edge of the foreign player movement.

Chelsea completed five of the 10 most expensive transfers in the history of English football. Manchester United have four, and Liverpool’s recent contract for Fernando Torres cost them 20 million pounds ($40M US). That’s not his salary, Americans; that’s just how much they had to pay to his old team. Yes, in Europe they’re buying and selling men, with no ethical notion of a player being his own entity and no apparent ceiling on how much can be spent.

In October of last year, Chelsea won 6-0 over Manchester City with players it had bought from Real Madrid, Bayern Munich, and AC Milan. . . sitting on the bench. This is a tycoon’s game. I drink your milkshake, there will be blood, give me your best players. (Chelsea’s owner is literally an oil baron, for Christ’s sake.)

The gap between football rich and football poor is pulling apart and swallowing most of the Premier League clubs. The only hope teams have is that eccentric foreign billionaires arrive and start signing ridiculous checks. Clearly, if there is one large problem with English football, this is it.

Right?

…

A dim, shiny head

Joseph “Sepp” Blatter has been FIFA’s bald head for 10 years, and football’s popularity has grown in spite of his best efforts. Blatter’s shown impotence or ignorance of football’s minor issues – wild over-spending, slimy deals penned by street agents, match-fixing, crowd safety and racism – to take on the real enemies, like altitude. And the European Union.

You see, the EU has this notion that if you’re talented, and someone wants to hire you, you should be allowed to work for them. Disgusting, I know. Good thing we’ve got Sepp, who braved the cutthroat field of Swiss public relations, around to stand up to injustice.

Blatter recently came out in support of a proposed referendum to limit English teams to a starting lineup of six native Brits and five foreigners. Sepp, who usually consults his five richest friends before he decides if it’s raining, was appealing to a growing group of English owners and managers who don’t own a world atlas. They want to be able to recruit in their own neighborhoods and field teams of their own boys. They say this is for the good of English football.

Some critics of the idea have alleged xenophobia, while I have alleged that xenophobia is a long word for racism.

Blatter’s support should be vilified for its racist leanings. And it should be ridiculed because it’s bullshit.

Of the 24 players to win the presitigous Ballon d’Or (Golden Ball), the award given to the world’s finest player, 16 played outside their country of birth. Of the last 30 players to finish in the top three for voting in the FIFA World Player of the Year, 24 were away from home.

Since Arsene Wenger’s been the Lord of North London, there have been three World Cups. Let’s work backward, one at a time.

In 2006, Germany, Portugal, France and Italy were the World Cup semifinalists. Portugal’s semifinal squad featured starters who played professionally in Russia, Germany, Italy, France, Spain, three from England, and only one who played in Portugal. Germany, which has, like Italy, been successful with a mostly self-contained talent pool, did start one key player who worked in England. Arsenal goalkeeper Jans Lehman was a goal-spoiler throughout, and he guessed right on two penalty kicks against Argentina to move the Germans into the semis.

While Italy’s team was entirely homegrown, their French opponents, who came thiiiis close to winning, had a roster of 11 players rooted in France, seven in England, and three in Italy.

In 2002, Turkey, South Korea, Germany and Brazil reached the semifinals. In its semifinal loss to Brazil, the Anatolians started two Turks who played in England, three who played in Italy, and another in Germany. South Korea, which shared hosting duties with Japan, assembled a roster of almost entirely Korean-based players. But every single goal on its improbable run came from a player whose checks came by international mail.

Again, Germany, the tournament’s runner-up, holds onto its best players. But the World Champion Brazilians had all 11 of their goals come from players in European leagues.

I know, I know. Football is about more than goals, and the Brazilians got a giant contribution from an unsung midfielder. At the time he played for Atletico Mineiro, in booming Belo Horizonte. But Gilberto didn’t stay in Brazil long. Some Frenchman convinced him to go play in North London.

In 1998, your World Cup semifinalists were Holland, Croatia, Brazil and France. Eight of Holland’s 12 goals in that tournament came from Dutchmen playing outside their homeland, including all five goals in the knockout stages. For Croatia, nine of its 11 starters and nine of its 11 goals in the tournament came from foreign-based Croats, including all five of its goals in the knockout round.

Brazil scored 14 goals on its way to the Final, and all but Bebeto’s three came from Brazilians playing in Europe. France, the 1998 Champions, had eight of its 14 goals, including its last five come from Frenchman who played outside France. Three of its homegrown goals came from Thierry Henry, who one year later went to North London to play for his old coach.

. . .

Connections and disconnections

At the tail end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th, a short, fat man, born on a small island, set out to conquer France. And then, the world. Fate brought him to a grassy field not far from Waterloo, in Belgium, where he failed.

At the tail end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, a tall, thin man, born in France, set out to conquer a large island. And then, the world. Fate brought him to a grassy field not far from Waterloo Bridge, in London, where he succeeded.

It hasn’t been easy, and it hasn’t always been pretty. Last season, Arsenal’s wheels loosened considerably in January of 2007 with an injury to Van Persie, the unsurprisingly creative son of a sculptor and a painter. In February the wheels flew off when Henry went down.

From late February to early April, Arsenal, the team that doesn’t lose, did, dropping six of nine games. The rudderless Gunners suffered a wicked 10-day spin, losing out of the Carling Cup, FA Cup, and Champions League.

It got worse. In May Arsenal’s charismatic director, David Dein left the club. He was followed in short order by Thierry Henry, who cited Dein’s departure and his unproven, babyfaced teammates on his way out the door toward Barcelona.

Arsenal’s hopes for 2007-08 would fall to a few players. Its goals would have to come from Adebayor, Rosicky, Van Persie, and the young Eduardo da Silva. For wildly different reasons, they've had rough years. And yet, Arsenal finds itself in a race for the Premier League title.

Van Persie sparked and caught fire early, seven goals in 10 games, before another knee injury in October. He’s tried to come back twice, and twice Wenger has sent him back to the bench for his knee’s sake.

Rosicky's been great this season, when he’s made it to the field. But the Czech has fought a losing battle against injuries, and has been missing since late January.

And then there’s the tragedy of young Eduardo. The pocket-sized Brazilian played his way out of Rio and took a ticket to Croatia when he was 18. After spending five of the last six years there —and with no opening cracks in the Brazilian national team — it’s reasonable that he took up Croatian nationality.

In the wake of Arsenal’s injury woes, Eduardo was rushed into the first XI, where he thrived. In his first 22 starts for Arsenal he scored 12 goals and assisted on eight others.

Then, three minutes into a match against Birmingham City two Saturdays ago, Eduardo took a pass and turned toward the defense. He shuffled his feet and made a typical, short Arsenal pass. Just then, a step late, Birmingham’s Martin Taylor slid in with his foot at Eduardo’s shin level.

Eduardo crumpled. Wincing in pain, the young Croat looked down at his foot and blacked out.

I’ll spare you the pictures. Suffice it to say, after Eduardo was rushed to the hospital, a series of doctors performed a series of procedures that prevented an amputation. In a single sickening moment Arsenal had watched its season, Eduardo’s young career and his foot, disconnected. The ashen players and their coach looked like they’d seen the ghost of Eduardo’s foot.

It got worse. After Walcott scored his first two goals, the second of which looked like a gamewinner, Gael Glichy was harshly penalized for a last-minute tackle in the penalty area. James McFadden converted the penalty.

Arsenal, which gave up a single shot on goal during the entire match, drew, 2-2, on the same day Manchester United walloped Newcastle 5-1 to tighten the race for first place. Afterward William Gallas, who experienced Arsenal’s 10 days from hell in 2007, who’s lost in a World Cup Final, sat on the ground, inconsolable. He’s not a surgeon, so the only thing he could do for Eduardo was win. And they didn’t. (There’s no good news about Eduardo. Done for the season, and I assume forever, though I hope I’m wrong.)

Now, to the Togolese forward. Adebayor was the coolest finisher in the world at the end of last year and the beginning of this one. But lately his head has let him down more than once, and in more ways than one.

His yips came back in the form of a rash of missed opportunities. In mid-January, he lashed out at his teammate, Bendtnder, headbutting him during a 5-1 loss to Tottenham.

Sadly his head couldn’t find the same accuracy in Arsenal’s next Champions League fixture against AC Milan. When a last minute cross found Adebayor unmarked, he missed a point blank header that would’ve given the Gunners a 1-0 scoreline at Emirates Stadium. Instead it finished 0-0; in order to advance, Arsenal would need to be the first English team in history to beat AC Milan in Italy.

One week before Eduardo’s injury, and four days before Adebayor’s miss, Arsenal took a message-sending 4-0 thumping from Manchester United in the FA Cup. It was humiliating. Adebayor’s miss was discouraging. Eduardo’s injury, crushing. The wheels had come off again. And how cruelly.

. . .

Part III – But it bends toward justice

The weak threads

At the tail end of the 19th century and the onset of the 20th, a group of French painters began leaving bold streaks on white canvas. What they did was altogether new, a revolution in expression.

As we do, we labelled them for our own comfort, eventually settling on the Impressionists. The term came from a work called Impression, Sunrise by Claude Monet, one of the movement’s founders. Monet’s vision and detail made extraordinary scenes from the ordinary.

The Impressionists worked in sunlight. They played new games with color and angle. Up close the power in their subtle brushstrokes was lost. Their work was best seen from a distance.

They were misunderstood upon their arrival. Dismissed, even. They changed painting forever.

Fast forward a hundred years. Art is alive, well, and still misunderstood. And there, in Geneva, Switzerland, the nexus of reasoned diplomacy, a dictator is cracking down. Not on the laissez-faire stylings of the world’s richest men, but on the last-ditch opportunities of its poorest.

I’d love to debate Sepp Blatter on the issue of foreign-born players, but he’s making all of my points for me.

What’s that you say, Sepp?

“Workers in Europe can circulate freely but footballers are not workers.”

Uh-huh. And?

“You cannot treat a footballer like any normal worker because you need 11 to play a match –– and they are more like artists than workers.”

Agreed. In the United States, we’re worried about an influx of millions of foreign workers doing work that almost anyone can do. Though I question the tone, when this trend worries Americans, I say it’s fair. In England, they seem worried about hundreds of foreign workers coming into the country to do work that almost no one can do.

Artists, you say, Sepp? Why, then, was a young French painter named Claude allowed to pass through London not once, but twice? Whither the English painters? Weren’t they threatened by his presence? Or were they inspired?

Artists, you say? Why, then, did the Courtald Gallery in London set a centerpiece exhibit around Monet’s disciple, Pierre-August Renoir a few weeks ago? Did they need to put up six English paintings for every five of Renoir’s? Did Brits question its origin? Or did they just stare and think, “Damn that’s pretty. . .”

Getting to Zimbabwe’s athletes is one of the more wrong-headed tactics being considered to push the aging despot Robert Mugabe out of office. (I’d suggest a wheelchair.) Among those affected would be Benjani Mwaruwari, whose 13 league goals for Manchester City have him fourth among scorers.

Let’s think about this. In order to get to one of the world’s worst-run countries, a country that’s literally running out of wheat, a country whose currency is more inflated than Blatter’s shiny head, where every night hundreds of people huddle together like wildebeest and cross a croc-filled river to get into South Africa. . .we’re going to take one of the only Zimbabweans making any real money. . . and send him back?

At the onset of this year’s Premier League season, only 37 per cent of the Starting XI players were English. If current trends continue, by 2020, -5 % of Premier League players will be loyal to the throne. That’s a punchline, and I hope it hits Blatter in the nose.

The thing is trends like this don’t bear out. The line does not fall to zero. At some point it curves and levels off. And besides, the Football Association should not be wondering how to get foreign players out of the England league, but about how to English players out of England.

By the way, the one country that has enough good and great players to fill its own domestic league with talent is the one country that tries to export them all. How’s that workin’ out for Brazil?

Look, there’s no player in the world, save Ronaldinho, whose skill equal does not exist in England. In the 2002 World Cup, England went out to Brazil, which is always excusable. But that team was timid in front of goal, and even its exciting young players seemed to be dragging a ball and chain.

In 1998 and 2006, against Argentina and Portugal, England had key players — David Beckham in ’98 and Wayne Rooney in ’06 — get red carded after onfield meltdowns. Both times England lost on penalty kicks, in what has become a tragic pattern for the island’s football.

Why would professional players who play high profile matches every week suddenly lash out so destructively? Why can’t England make its penalty kicks? How could David Beckham miss 10 feet high on a 36 foot shot, as he did at Euro 2004? Might the players feel the pressure of the foaming English fans and bloodthirsty tabloid press?

The fault, dear brutes, lies not in your stars, but in yourselves. There’s nothing wrong with English footballers, and a lot wrong with English football.

. . .

But still, like dust

Only a week after their dust up, Adebayor and Bendtner were together on the field again when the Dane came on as a 71st minute sub against Newcastle. With his very first touch, Bendtner flicked a header toward Adebayor, who tried to find Bendtner with a return pass. It missed, but only seconds later Matthieu Flamini scored an outrageous goal to put Arsenal ahead 2-0, and it seemed that all was well in North London.

Seven minutes after that, Bentdner offered a typical short, unselfish Arsenal pass to Cesc Fabregas, who converted to make the score 3-0 and guarantee that Arsenal would pass Manchester United to top the league. Adebayor wrapped a gentle arm around Bentnder, and whispered something into his ear.

It would be foolish to say that the two will someday be best friends. But clearly, they could be teammates.

That game was followed in short order by the 4-0 loss to Manchester United and the injury to Eduardo. If they had in fact turned against Arsenal, the fates seemed ready to turn the screw when the Gunners hosted Aston Villa on the first day in March.

Only minutes after flubbing a chance for a rare goal, Philipe Senderos was dealt a brutal fortune. In the 27th minute, Villa’s Gabriel Agbonlahor dribbled toward the endline and rolled in a hard pass. Senderos’ foot betrayed him, and the ball deflected into Arsenal’s net. Senderos doubled over. At the end of an awful week, cameras caught him seeming to wipe away a tear.

Down 1-0, Arsenal began to find space, and each other. A number of offensive moves saw the final shot stopped by Villa keeper Scott Carson or whiz over the crossbar. Fabregas, Glichy, Hleb, Flamini and Adebayor all came close. On the other end, a resurgent Senderos made a difficult clearance to keep the Gunners from going two goals down.

But with twenty seconds remaining, Arsenal still trailed by a goal. On the left side, Fabregas threw in to Hleb, who gave it back. Fabregas rolled a short pass back to Glichy, who curled a cross into the box.

Adebayor rose. He nodded the ball down, toward a teammate.

Just as the ball touched the ground, Bendtner rolled his shot into the corner of the net. 1-1, and with seconds left. The point earned meant that Arsenal would finish the day still in first place.

The camera showed Arsene Wenger, gleeful, raising his fists above his head, and I realized I was smiling.

. . .

Epilogue - Self-evident

When confronted with the idea of limiting foreign players in English football, Arsene Wenger said the kind of things you’d like to hear. Not from your favorite football coach, but from your favorite philosopher.

“Sport is competitive and competition is based on merit,” he said. “It does not matter where you are born, it matters who you are.”

And it matters who the coach is. Wenger’s players have looked too old, too young, too hurt, or too different to win. But they’ve won, and now some narrow-minded prats want to stop them.

Wenger was 18 on the Night of the Barricades. Alas, they were in Paris, and he was a student in Stasbourg. He wasn’t on the barricades that night. But he is now.

Maybe for every step he takes, Wenger sees someone else take a step backward. Maybe he sees the recent labor strikes and race/class riots in France, and fears for his country, and its fearful leader. Maybe he hears a growing anti-Muslim sentiment in the West. Maybe he hears a growing anti-Western sentiment everywhere else.

Maybe he sees that people the world over are taking advantage of increased transportation and freedom — not just moving to be near people who are similar, but to get away from people who are different.

Or maybe he sees positive forces, too, like the fact that Viktor Bout and Charles Taylor are no longer free men. Or that, 40 years after George Wallace got four states and 10 million votes, the third black U.S. Senator in the last century is running for president, and 130 delegates to the good.

As a man of science, Wenger might have seen the growing amount of biological evidence that the difference between all humans, from the palest Belarusian to the darkest Ivorian, is negligible.

Maybe he thinks about none of those things, and only wants what we all want: goals. He didn’t and doesn’t make speeches about changing the face of English football. Wenger did not bring the Premier League into the modern era, just Arsenal. He is a man on his own time.

But Wenger’s assembled a group of young men who work together, and beautifully. They are the United Nations of Football. A coalition of the willing to pass and move. A nonviolent nongovernmental organization, out to conquer the world. Teammates sans frontieres.

The only imaginary line they see is the one they’re on: the path that takes the ball to the goal. Sometimes direct, more often abstract.

Wenger has brought them to England, a country that’s thrived for 500 years — not on its own raw materials, but on its ability to turn separate parts into a finished product; he’s brought them to London, a port that thrived not because of its defensive position, but because the Thames is so easily navigable.

Forget the way they've synced-up so compellingly. These players, from these disparate places, would never have met without football, and without Wenger. And for whatever reason, some of his very best players begin to ask, “What’s with all this hate in the world?”

He’s fielded a last line of defense that hailed from Manchester, Oxford, South Yorkshire, and London. And another from Geneva, Bouake, Abidjan and Tolouse.

Wenger’s united players from the divided West Coast of Africa, awoken the sleepy Spanish shores of the Mediteranean, broken up the milky white homogeny of Switzerland and Denmark and found a beam of light streaking through the clouds north of the Thames. E pluribus, unum.

A lot of historians don’t think any one of us can be an agent of change. Perhaps they give little weight to the “great man” theory because, taken in full, so few of us are actually great.

Like their opponents, agents of tolerance must dig in to gain footholds. They must pull at the weak threads of racism’s and nationalism’s arguments, wedge our humanity against our cruelty, turn youthful passion to beauty, and not hate. They must conquer minds. Not by fear, but by acts of inspiration, whether that’s a series of angled passes in London, or an enormous message from a French or Liberian star, or a small, whispered message from one man’s mouth to another’s ear.

Wenger is signed on to stay in North London for at least eight more years, though he jokes about staying forever. We should be so lucky.

(Author's note: During the writing and editing of this piece, Arsenal won a historic 2-0 win over AC Milan to advance in the Champions' League, and a 0-0 draw against Wigan means that Arsenal are still on top of the Premier League and, for the moment, the world.)